HMAS Leeuwin – A History

HMAS LEEUWIN – Where Teenagers become Men in 12 short months

History – HMAS Leeuwin

Leeuwin, the Dutch word for lioness, is also the name of the Dutch vessel that made landfall in Western Australia in March 1622. The term ‘Leeuwin Land’ was applied by some to the entire south western region of the State, but the explorer Captain Matthew Flinders, gave the name, more precisely, to a large cape he described as the southern and most projecting part of Leeuwin’s Land. So Leeuwin actually refers to the cape which brought Western Australia to the mind of all seafarers.

The permanent RAN presence in Western Australia had been relatively small and Leeuwin did not become its focus until August 1940. In 1913 a building known as King’s Warehouse was leased by the RAN and used as a drill hall for 13 years until the District Naval Officer and his staff moved to a new hall, constructed on a block of land in Fremantle bounded by Mouat Street, Croke Lane and Cliff Street. This facility was originally known as Cerberus (V), a name which signified that it was a tender or sub-element of Cerberus located far away in southern Victoria. On 1 August 1940 the Mouat Street site was commissioned as HMAS LEEUWIN.

The official badge of Leeuwin is based on the Dutch royal coat of arms the motto of which translates into English as ‘I Shall Maintain’. The badge shows a crowned and rampant lion clutching a sword and shield.

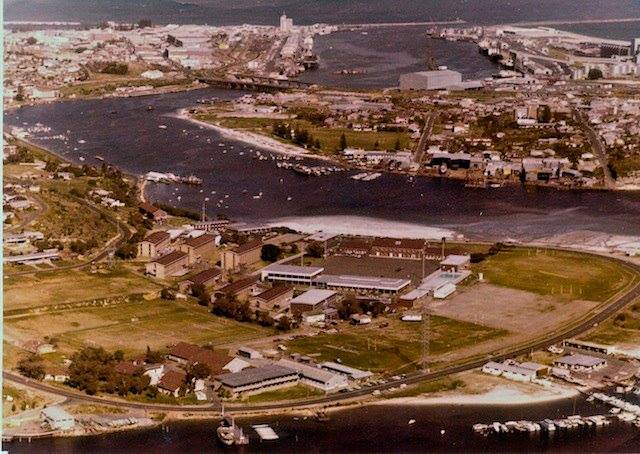

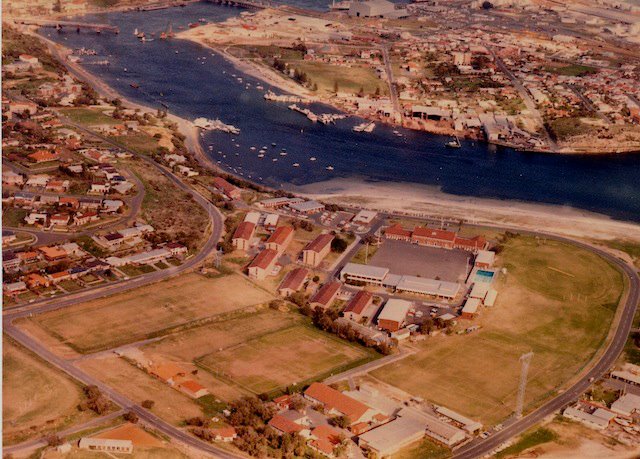

From January 1960 to December 1984, nearly 13,000 boys aged 15 to16 years old joined the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) as Junior Recruits (JRs) to complete a year of training in the Junior Recruit Training Establishment (JRTE) located in HMAS Leeuwin, on the banks of the Swan River at Preston Point in Fremantle, Western Australia.

Before Leeuwin

The recruitment process of assessing scholastic potential, assuring medical fitness and conducting a psychologist’s interview began the boy’s interaction with the RAN. It seems to have been a very straight forward and smooth process with very few ex-junior recruits having unpleasant or otherwise noteworthy memories of it. The assessment of physical and health fitness, undertaken as part of the recruiting process, was not onerous but former junior recruits do recount the usual tales of being invited by the doctor to bend over for a rear end inspection and of their surprise at being grasped by the testicles and invited to cough. After being selected for entry, some boys clearly remember swearing an oath at the Recruiting Centre on the day of their enlistment, while others are certain they were not required to do so.

Travel to Leeuwin was an adventure for most JRs who had little or no experience of either long distance travel or absence from home. For JRs recruited from the south west of Western Australia it was straight forward: assembly in Perth with other Western Australian recruits followed by an overnight stay in the YMCA before being bussed to Leeuwin the next day to join their colleagues from other states. For JRs from the other states it entailed up to six days of second class train travel, without ‘sleepers’, before the Navy in 1967 stopped regarding air travel as an expensive luxury. For the 47th Intake (1974), travel to HMAS LEEUWIN from the eastern states involved a chartered flight that started in Queensland on the morning of 22 April 1974 and arrived in WA around midnight (WA time) via Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide.

Induction

Many junior recruit’s initial experience of Leeuwin was that of bellowing instructors, uncertainty, disorientation and homesickness. The late-night arrival of entrants from the eastern states exacerbated many JR’s concerned feelings over ‘what they had gotten themselves into’.

Hair Cuts

New junior recruits shared an experience endured by probably every military recruit the world over – their first military haircut. Leeuwin had two barbers under contract who were, due to their names and accents, referred to by most junior recruits and staff as ‘Von Snips’ or simply ‘Snips’ and his son ‘Snips Junior’. Every junior recruit had a standing appointment every second week for a short back and sides ‘Leeuwin style’ haircut and during each working day the barbershop was the scene of a production line as the JR’s hair was cut swiftly at low cost. For the newly enlisted JRs, the 1960s and 1970s long hair styles were transformed quickly into the haircut they would sport for almost the remainder of their naval career. Often much to the amusement of the other JR’s (as the barbershop (in 1974) was adjacent to the entrance to the Dining Hall).

Kit-Up

What to an outsider would appear a simple process of providing the JRs with the required number of uniform items became a two-stage ritual and for many JRs, an unpleasant one as it was usually conducted by distinctly unsympathetic senior sailors, principally of the Stores Victualling branch.

Stage one occurred in the clothing store where JRs were issued with many often-unfamiliar items of uniform and uniform maintenance items. Many of the items – naval blue jean collars for example – were simply unrecognisable to most JRs. Commencing with the issue of a thick canvas sailor’s kit bag, each junior recruit had to receive, try for size and stow in the kitbag virtually all the items that would clothe him for the next year or more. Having done so, each boy locked his bag and staggered off under its weight back to their accommodation, to make sense of it all.

In the second stage, which seems to have varied in process over the years, each JR was placed at a desk or ‘station’ in Leeuwin’s drill hall. Each station was equipped with an alloy name stamping device prepared with his name and two pads of cloth, one impregnated with black paint and the other with white paint. With navy kit consisting almost entirely of white or black items, the white paint was to be used to mark the black ones and black to mark the white ones. Kit items had to be marked in the precise location identified by the senior sailor conducting the whole activity. Opportunities for error abounded: the wrong colour paint could be used, an item could be marked in a non-approved position or marked in a messy or indistinct manner. The error rate by the JRs was proportional to the declining composure and increasing frustration of the shouting and swearing senior sailor conducting the activity.

Uniform

After receiving their issue of naval uniforms shortly after arrival in Leeuwin the JR’s had to send home all their civilian clothes, except underwear. While JR’s who came from Perth or nearby, and some who were sponsored by local families, did have access to civilian clothing, most JR’s possessed only the navy uniform clothing that they would wear for almost the remainder of their year. In the early days JR’s wore the TINGIRA flash on both shoulders of their uniforms. Later in the 1960s, after the introduction for all Navy officers and sailors of shoulder flashes bearing the word ‘AUSTRALIA’, the TINGIRA flash was placed immediately beneath the ‘AUSTRALIA’ flash on the right shoulder. Wearing the TINGIRA flash served the triple purpose of providing a link back to the JRs of the training ship moored in Rose Bay, distinguishing them from their adult junior sailor colleagues and, to the chagrin of junior recruits but no doubt to the approval of their parents, advertising them to the public, to Naval and civilian police and to publicans as minors under the legal drinking age.

All JRs had to sew flashes on each shoulder of almost every one of their new jackets, shirts and ‘white fronts’ – the traditional sailor’s tee shirt worn as outer wear in summer or under a seaman’s black jersey in winter. Sewing was done using a ‘housewife’, a 20-centimetre square compartmented navy sewing kit containing black and white cotton and needles. When not in use it was rolled into a small cylinder for ease of stowage in a sailor’s locker. For JRs accustomed to having their mother mend and alter their clothing the need to sew was a shock that frequently produced gross insults to the tailor’s art.

Within Leeuwin junior recruits wore plain black and ugly leather ankle boots that were expected to be always kept in a high shine and spit-polished for parades and other ceremonial events. The two pairs each boy owned wore down rapidly from jogging to and from classes which meant frequent resoling, a task that in the late 1960s was alleged to have been done by prisoners in Fremantle jail. Webbing anklets and belts were worn during working hours also. Until late in the scheme when black items were introduced, webbing was whitened with a daily application of ‘blanco’. The brass buckles and removable clips were expected to be highly polished in readiness for morning ‘colours’ parade on working days. Many former junior recruits complain that this unrelenting daily attention to cleaning webbing either put them off uniform cleaning forever or produced an opposite effect, one of personal sartorial fastidiousness that lasted throughout their naval careers into civilian life.

In July 1976, the privilege of wearing civilian clothes while on short term leave in Western Australia was extended on a trial basis to the senior class of junior recruits during the last three months of their training. The aim of the trial was to ease the transition of junior recruits from Leeuwin’s closely controlled and regulated environment to the less restrictive, more adult, milieu that existed in the ships and bases in which they would serve after leaving Leeuwin. The trial was regarded as a success and junior recruits in the final months of their training continued to enjoy the privilege until the training scheme’s conclusion.

JRs selected for higher education and transfer to the topman scheme wore, as did upper yardman officer candidates, uniform devices to distinguish them from junior recruits and ship’s company members. In summer uniform these were blue strips of cloth about an inch wide and four inches long attached ‘fore and aft’ on both shoulders. In winter uniform, white stripes were worn in the same position, a practice which led junior recruits in the late 1970s to refer to them as ‘band aid JR’s. Topmen lived a life almost separate from the junior recruit population wherein they undertook academic studies throughout the day and each evening from Monday to Friday, and on Saturday mornings. Except for some participation in sports and limited drill instruction with the heavy cutlass, their lives in Leeuwin were devoted to academic studies.

Medical

Injections and inoculations against a range of diseases were also conducted by a production line approach wherein JRs filed past sick bay staff who took turns until each boy had received the number of needles he required. Fainting was common and for those who did not cope well with needles, it could be a very unpleasant experience. Sore and scabby arms added to the JR’s woes for a few days thereafter.

Accommodation

Construction of the first of seven multi-story brick accommodation blocks began in 1963. The blocks were intended to represent the stark but much more cluttered and less spacious environment of the shipboard mess deck in which the JRs would live post-Leeuwin. Designated with the letters A to G, each block could house 200 JRs with up to eight living in each door-less cubicle situated either side of a central corridor. Heads, showers and a laundry room were located at one end of each floor. Offices for divisional staff members were located immediately inside the ground floor entrance of each block. While a significant improvement over the original accommodation, the new blocks were not particularly comfortable places in which to live. There were few showers, with the ratio of JRs to a shower varying over the years of the scheme between 12 and 25 to one. Laundry facilities remained barely adequate. Even given the better standards provided in the new blocks conditions were such that early in 1972 the incoming NOCWA expressed his surprise at the ‘spartan nature of the accommodation blocks’ and his desire to make them seem more homely.

Within cubicles each boy was allocated a bunk and a four-compartment locker in which all his possessions except his bedding, towel, cap and raincoat (known as a Burberry) had to be stowed. Sheets were issued as ‘loan clothing’ and one sheet was washed in a laundry service once a week. Bedcovers – ‘counterpanes’ in navy jargon -were washed once a term. For the washing of uniforms, a laundry was located within the accommodation complex. This was equipped with Lightburn brand, ‘cement mixer’ style, washing machines and drying rooms heated by electric fan heaters.

Initially JRs were not permitted to leave personal items outside their lockers nor were they permitted to decorate or otherwise personalise their cubicle with photographs, posters or other items. Immediately after ‘WAKEY WAKEY’ each morning each boy had to strip his bed and fold and place all his bedding in the regulation folded manner atop his mattress where they stayed until beds could be readied for use after evening inspection – ’rounds’ – by the duty officer. Clothing or personal items left lying about – ‘sculling’ – were removed to be later collected from a staff member along with a fine, an oral censure or worse.

Accommodation was patrolled at night by Duty Divisional Staff/Coxswain/Naval Dockyard Police who did a bed check and provided a general security service although in the view of some JRs they often took their role too seriously. The ‘turning out’ of complete divisions at night was not unusual because of noise or unruly behaviour and duty divisional staff would often be seen running JRs around the parade ground at all hours.

Pay

In November 1907 ‘Harvester’ ruling a fair and reasonable minimum wage for Australian workers was set at seven shillings per day. In 1960 pay was age-based with junior recruits younger than 16 receiving nine shillings and two pence per day. On turning 16 their pay increased to fourteen shillings and two pence per day. At the age of 17 they received one pound and six shillings per day. JRs of 17 also received two shillings and six pence uniform allowance per pay but were responsible for the upkeep of their kit unlike younger JRs who received free uniform items to replace those damaged through fair wear and tear. A summary of the JR’s pay and pocket money rates over the years is shown in Table 1.

| Year | Junior Recruit 2nd Class/Boy 2nd Class |

Junior Recruit 1st Class/Boy 1st Class |

| 1912 | £0/14s/0 gross, 2s pocket money | £1/1s/Od gross, 3s pocket money |

| 1960 | 15-year-old – £4/11/8 gross, 15s pocket money 16-year-old – £7/1/8 gross, 15s pocket money |

16-year-old – £ 7/1/8 gross, £ 1/0/0 pocket money 17-year-old – £ 14/4/6 gross including uniform allowance, £1/0/0 pocket money |

| 1970 | 15-year-old – $18.76 gross, $10 pocket money 16-year-old – $26.04 gross, $10 pocket money |

16-year-old – $26.04 gross, $12 pocket money 17-year-old – $28.93 gross including uniform allowance, $12 pocket money |

| 1980 | $65.00 | $87.00 |

Table 1: Fortnightly Pay Comparison

Until 1973, JRs did not receive all their pay in hand. Instead, like their Tingira forebears, they only received pocket money in hand with the balance of their pay deposited into a Commonwealth Bank account opened by the RAN on their behalf. Each boy’s account passbook was handed to him shortly before his departure from Leeuwin after passing out. A further stipulation was that junior recruits were not to have large sums of money in their possession. Early in the 1960s junior recruits second class were not permitted to have more than £ 2/0/0 in their possession at any one time while a junior recruit first class was permitted to have not more than £3/0/0. Compulsory banking was abolished by Naval Board decision in 1973 prompting the NOCWA to observe in October of that year that many JRs were:

“Squandering their pay on expensive consumer items and offences involving alcohol are increasing. Nevertheless, I believe that the Naval Board decision will have the effect of cushioning the dramatic rise in pay when adult rates are received after they leave Leeuwin and therefore in the long term the decision will be of benefit.”

While many former junior recruits recall always being short of cash and having to borrow from family and mates, they did not actually need much money to survive in Leeuwin -providing they did not smoke or over-indulge in soft drinks or lollies. Cleaning materials for uniform maintenance and hygiene items were the biggest drain on their income but it was not until 1980 that each boy’s pay was ‘docked’ a small amount to cover ‘LWF’ – laundry, welfare and haircuts. As was customary in the armed forces at the time, all JRs received free food, accommodation, medical and dental treatment and paid annual leave travel. The JRs received their pay every second Thursday in the traditional naval manner. Having fallen in alphabetically, at the accommodation block, each boy, on hearing his name called, marched forward to the Divisional/Supply Officer to salute, show his identification card, call out the last three digits of his service number and receive his pocket money in a small manila envelope.

Divisional Structure

Leeuwin junior recruits of the same division were accommodated together and led by divisional staff usually comprising a Divisional Officer, normally of Lieutenant Commander or senior Lieutenant rank, assisted by Divisional Senior Sailors usually of Chief Petty Officer and Petty Officer rank.

In 1960 training began with five divisions, each named after a prominent Western Australian aborigine of the early 19th century: Kaiber, Mokare, Nakina, Winjan and Yagan. As the numbers of junior recruits undergoing training increased and as the Navy continued to have difficulty in providing experienced divisional officers, new divisions were formed, new names were added, and old names discarded. In 1965 use of the aboriginal names ended and the practice began of naming divisions after former RAN officers. Initially Collins, Morrow, Howden, Rhoades and Morris were used, with Marks, Stevenson, Walton and Ramsay added later.

Ramsay Division was formed in 1972, thereby commemorating Commodore James M Ramsay, the NOICWA and Naval Officer Commanding Western Australia (NOCWA) from January 1968 to January 1972. The practice of using the names of former RAN officers continued until the end of the junior recruit training scheme in 1984 although, as intakes increased or decreased in size, divisions were sometimes further sub-divided into ‘port’ and ‘starboard’, or into numbered sub-divisions such as Rhoades 1 and 2. For the 86th, and last, intake there was only one division, Ramsay, comprising 40 JRs.

Junior Recruit Training and Education

The Junior Recruit Training and Education process had two main components: schoolwork and naval training both theoretical and practical in nature. Schoolwork was to develop the JR’s ability to better comprehend technology and cope with the demands of their employment category training post-Leeuwin. Naval training was to prepare them for life and work in the RAN, particularly in warships.

Table 2 outlines the syllabus subjects taught over 30 hours per week in 1960:

| Naval Subjects | 16 Hours | Schoolwork | 14 Hours |

| Seamanship – Theoretical | 1 | English | 2 |

| Seamanship – Practical | 4 | Arithmetic and Algebra | 2 |

| Signals – Practical | 1 | Geometry and Trigonometry | 2 |

| Small Arms Practical | 1 | Physics | 4 |

| Parade Training | 4 | History | 2 |

| Physical Training and Swimming | 4 | Elementary navigation | 2 |

| Miscellaneous lectures | 1 |

Table 2: Syllabus at Leeuwin in 1960

Class Allocation

Initially allocation to classes A to F was based upon Leeuwin’s staff Senior Psychologist’s review conducted during the recruiting process. Five weeks after joining Leeuwin all JR’s sat Educational Test Number 1 (ET 1), a test of competence in English, Arithmetic and General Comprehension. Some JRs were reclassed because of their ET 1 results. The essential short-term difference arising from the class allocation was that those in an A class spent more periods each week on schoolwork while those in an F class spent more time on naval subjects and miscellaneous activity. In the longer term, classing up could be influential in determining the employment category to which JRs were allocated and whether they could be considered for transfer to apprentice or officer training.

‘Miscellaneous lectures’ exposed JR’s to a wide range of information, some of which was vital to their later welfare and efficiency while working and living at sea. Information covered in these lectures included: atomic, biological and chemical defence and damage control (‘atomic’ later became ‘nuclear’); survival at sea; first aid and health; pay and allowances; character guidance and religion; and naval indoctrination including branch and employment category familiarisation.

Records do not reveal exactly what the RAN planned to do to achieve all elements of its four-part aim of training young men so that they would:

- regard the Navy as their vocation,

- develop a high standard of discipline, trustworthiness, initiative, courage and endurance,

- reaching an educational standard that would enable them to assimilate their subsequent professional training, and

- eventually, being an important source of supply of petty officers, chief petty officers and Special Duties List officers.

However, a high standard of discipline and the inculcation of the desired values seem likely to have been regarded simply as natural outcomes of a process in which the JRs were exposed to the RAN, its lifestyle and its people, and were involved in the range of activities incorporated in the training plan. The latter included a strong emphasis on physical fitness training and sporting activities. Junior Recruits were also subject to almost daily parades and weapons drills, character guidance – largely by chaplains of various religious denominations – ‘expeditions’ or camps, and knowledge of and obedience to the Naval Discipline Act (later, the Defence Force Discipline Act).

In so far as having Junior Recruits regard the Navy as a vocation, it seems likely that the RAN subscribed to a variant of the Jesuit motto of ‘give me a child until he is seven and I will give you the man’, believing that recruitment as JRs followed by a year of naval indoctrination would produce men committed to a long-term naval career.

Junior Recruits at HMAS Cerberus

Between 1963 and 1965 two intakes of junior recruits were trained at Cerberus to capitalise on the excellent recruiting response. Increasing the number of JRs under training in Leeuwin was not possible because of the lack of infrastructure there, despite the work being done to upgrade accommodation and training facilities. Training for the first Cerberus intake of 125 JRs began on 17 March 1963. A second intake of 200 joined on 5 April 1964. The first intake graduated on 26 March 1964 while the second graduated on 1 March 1965, both with the loss of only two JRs. The extraordinarily good graduation rates suggest that the JRs commitment and the quality of the training received were both high.

Life as a Junior Recruit

It is impractical to attempt to describe the Leeuwin lifestyle experienced by junior recruits over the entire term of the scheme as it changed over the years, in an evolutionary rather than revolutionary manner. The most notable changes that occurred for junior recruits were improvements in living standards, accommodation, dining, recreation and sporting facilities. Changes to the JR’s education and training regimes were others, particularly the 1979 reduction in course length from a year to nine months. Also, evident would have been the impact on the entire RAN of the change in community attitudes and standards that occurred in Australia in the 1960s and the 1970s: hair was worn longer, civilian clothing was worn ashore more often and some of the traditions, customs and habits inherited from the Royal Navy had either been discarded or were falling into disuse as they became less relevant to the Australian Navy.

As well as being a school, Leeuwin was a commissioned naval establishment staffed almost entirely by officers and sailors of the Permanent Naval Forces and organised and administered in much the same way as other Navy training establishments. The Naval Discipline Act and the subsequent Defence Force Discipline Act applied almost equally to JRs and staff members alike. Life at Leeuwin was regimented and regulated, where formal and informal rules governed almost every aspect of life. Those who broke the rules were liable to punishments that boys in civilian boarding schools would find very harsh indeed.

On arrival in Leeuwin all new JRs were identified as being at the very bottom of the RAN’s formal rank hierarchy, with relative seniority determined by intake date. Unofficially, however, it meant much more to the JRs as it helped reinforce an informal but strong rank/hierarchical culture that the JRs maintained amongst themselves.

JRs (but not the staff) referred to the newest intake members as ‘new grubs’, the next senior as ‘grubs‘, the next as ‘shits’ with ‘top shits‘ assuming the position of superiority as the senior intake. It was not simply a matter of vulgar sailor nomenclature. As each intake progressed towards graduation it assumed for itself a level of higher status over the members of newer intakes and the right to claim privileges. The most common and relatively harmless, though extremely irritating, privilege was to ‘jack’ or move personnel to the head of the meal (SCRAN) queue.

Leeuwin’s training environment had two major functions. The first was simply to provide facilities to cater to the JR’s needs for accommodation, food, health care, recreation, education and training. The second was to accustom them to the environment in which they would have to live and work after graduating and being posted to sea. Leeuwin’s command structure was like that of a ship with a CO, an XO as second-in-command and Heads of Department responsible for supply and secretariat, education, training, health care and engineering. Daily Orders, a document promulgated each afternoon under the authority of the XO, set the pattern of daily activities and allocated staff and junior recruits to undertake a range of domestic functions. Junior recruits were required to know and use the traditional jargon used by sailors in ships: the main gate was the ‘gangway’, toilets were the ‘heads’, a floor was a ‘deck’ and walls were ‘bulkheads’. Meals were ‘SCRAN’ and individual dishes had names that would be remarkable if not offensive to the civilian ear. For example, tomato au gratin, a Navy cook’s breakfast favourite, was known as ‘train smash’ while savoury mince on toast was often referred to as ‘shit on a raft’. This adapting function was not unique to Leeuwin. It occurred in much the same way for cadet midshipmen at HMAS Creswell, for apprentices at HMAS Nirimba, and for adult recruits at HMAS Cerberus.

Leading Junior Recruits (LJR)

In June 1963, the position of Leading Junior Recruit (LJR) was introduced, partly because the under-strength staff was having difficulty undertaking all the necessary management and leadership tasks expected of it. A perceived need to offer some practical leadership experience to the JRs was another reason for its introduction. Personnel were selected based on their conduct and performance during the first term, JRs were appointed as LJRs at the beginning of the second term and discarded the ‘rank’ at graduation. Their principal duties were to assist staff to supervise cleaning of the accommodation blocks, minimise noise there after hours and lead formed squads of their division and class mates on the parade ground and while moving about the base during working hours. JRs appointed as LJRs wore distinguishing marks on their uniform which varied depending on the year they trained at Leeuwin. On their daily working uniform, they wore a coloured lanyard.

Routine

Although it varied over the years, a junior recruit’s stay in Leeuwin had three major parts: an induction period and two terms of study. A mid-calendar year leave period separated the two terms except for those who entered Leeuwin in an April intake. All JRs received home leave at Christmas. The ‘basic daily routine’ for the first intake of junior recruits was:

0530 Call the hands

0600 Fall in, clean ship

0655 Breakfast

0755 Fall in for morning parade

0800 Colours (ceremony of raising the Australian National Flag (ANF) and the Australian White Ensign (AWE)) followed by divisions (inspection and march past) and prayers

0815 First study period

0915 Second study period

1015 Stand easy (a break)

1030 Third study period

1130 Hands to bathe (swimming) in summer or physical training

1200 Dinner

1315 Fourth study period

1415 Fifth study period

1515 Sixth study period

1615 Tea

1630 Recreation

1845 Supper

1945 Commence evening preparation

2030 Secure

2100 Secure, clean for rounds

2115 Turn in (to bed)

2130 Rounds, lights out

This routine varied over the years. For example, call the hands was moved to 0600 and then to 0630, but regardless of the time late risers could find themselves clad in pyjamas and slippers double marching around the parade ground carrying their mattress and bedding. Rounds were advanced to 1900 and lights out was deferred until 2200 to give JRs more undisturbed time for study and recreation after completion of rounds. However, in a community comprised of large numbers of 15 and 16-year-old JRs ‘undisturbed time’ was seldom available to a boy intent on study.

Life was conducted ‘at the rush’. For new JRs each weekday morning was a time management nightmare wherein they had to shower, shave (not shaving was a punishable offence), eat breakfast, scrub and tidy their cubicle, and go to the armoury to draw rifles. After falling in by division on the parade ground they were inspected, participated in the colours ceremony and marched past. After the parade, held in all but extreme weather conditions, JR’s were double marched off by class for their first period of instruction.

In addition to being responsible for the cleanliness and tidiness of their own living spaces, all JRs shared the burden of communal domestic duties. They could work as kitchen hands, cleaners and scullery party in the dining hall; do garbage disposal duty; assist various staff members in a wide variety of base duties including gunner’s party, where they maintained the establishments many rifles; and acting as messengers, cleaners and general assistants in the many offices of Leeuwin’s administration organisation. Certain jobs, particularly those in some of the offices, were preferred over others as they involved little work and the opportunity to relax, to read and to drink as much coffee or tea as desired.

Men Under Punishment

A special routine applied for JR’s awarded a formal punishment. Those experiencing a period of punishment were, in navy jargon, said to be ‘on chooks’ and in daily orders were referred to as ‘MUP’ – Men Under Punishment. For them, private time was further restricted and the need to rush intensified by the inclusion of extra work and (usually fairly painful) rifle drill on the parade ground. For these JRs, the more incorrigible of whom experienced multiple punishments in their year at Leeuwin, their very tiring daily routine involved:

0530 Call the MUP

0600 Fall in at the Gangway for roll call and work detail

0645 Secure, re-join junior recruit normal routine

1230 Fall in at the Gangway for roll call and work or drill

1300 Re-join junior recruit normal routine

1630 Fall in on the parade ground for drill or work

1800 Re-join junior recruit normal routine

1900 Fall in at the Gangway for roll call and work detail

2100 Secure, re-join junior recruit normal routine

Drill and Ceremonial

Drill, usually with rifles, was a significant feature of the life of junior recruits. In addition to the parades – ‘divisions’ as the Navy calls them – there were ceremonial divisions conducted during working hours at regular and frequent intervals, church parades, leave inspection parades and quarterly graduation parades. Few JRs graduated from Leeuwin without having marched through the streets of Perth to mark an event or paraded as a member of a guard to welcome or farewell a visiting regal or vice regal dignitary. The JRs also marched on Anzac Day and to commemorate significant military events such as the Battle of the Coral Sea and Trafalgar Day. Drill at Leeuwin was, as a result, of a relatively high standard.

From 1960 to 1968 junior recruits drilled with and were taught to maintain and fire the Lee Enfield .303 rifle that had been the standard individual weapon of the Australian forces for most of the 20th century. Unloaded but with bayonet fixed it weighed about three kilograms and was over five feet long, about the height of many junior recruits. After Navy drill changed from shoulder carriage of rifles to the modern side carriage style Leeuwin’s .303s were modified by the addition of a wooden handle screwed to the magazine. While highly uncomfortable to use for prolonged periods it satisfactorily mimicked the handle of the rifle that would replace the .303 from 1967 the L1A1 7.62mm self-loading rifle (SLR). Weighing about the same as the .303 the SLR had a much shorter bayonet and was therefore easier to manage and much more comfortable to use than its predecessor.

Leave

Like their adult sailor colleagues, junior recruits were entitled to two types of leave – ‘seasonal’ and ‘short’. Seasonal leave was taken mid-term by all JRs except those who entered in an April intake while the Christmas break applied to all JRs.

Short leave refers to that taken on a weekly basis. Junior recruits’ entitlement to short leave varied throughout the duration of the scheme. No boy was allowed any leave during his first few weeks at Leeuwin – the ‘initial training period’. Later they were granted leave on Saturdays and Sundays providing they were not undergoing punishment or required to remain on board for domestic duties as part of the Duty Watch, a commitment that recurred every four to six weeks. Short leave began to be granted on Friday nights in 1971 in an effort to make the Leeuwin lifestyle less restrictive. Leave expired at 2200 for junior recruits second class and at midnight for first class JRs, with late return invariably attracting a formal charge and punishment unless a very good excuse could be given. Exceptions to this rule were JRs with homes in the Perth and Fremantle region and those JRs fortunate enough to obtain ‘sponsors’.

For almost 24 years, Leeuwin staff ran a sponsorship scheme in which JRs, particularly those from states other than Western Australia, could spend leave with families residing in Perth, Fremantle and nearby country areas. Sponsorship allowed JRs, with the approval of their parents, to stay overnight with carefully selected families. For the JRs it offered some respite from regimented life in the blocks, an opportunity to change out of uniform into civilian clothes and the chance to talk to females. Many families sponsored multiple JRs over the years, producing life-long friendships, correspondence and, in some case, marriages between JRs and daughters of sponsor families.

For JRs without sponsors and with little cash in their pockets, there was not a great deal to do while on short leave. While much of Fremantle, particularly the area of hotels in the west end of the town, was out of bounds, it did attract JRs seeking to purchase alcohol illegally with the assistance of unscrupulous or mistakenly sympathetic hotel staff. Many JRs frequented the Flying Angel Club built in Fremantle in 1966 on the site of the Eastern Seafarers Club first established in 1943 to cope with a wartime influx of Asian sailors. While not the sort of place normally associated with youth entertainment the Flying Angel was within easy walking distance of Leeuwin and constituted a ready refuge from their daily rigours where the JRs could play billiards, or the juke box and savour cheap take away food and drinks.

Health

Whilst at Leeuwin, as in the Fleet, great importance was placed on personal hygiene, the cleanliness and neatness of uniform, and of accommodation. Both were inspected daily, and staff members were quick to issue kit musters to JRs who failed to meet the standards required. Naval standards were difficult to accept and achieve for many of the JRs whose mothers had formerly done all their washing, ironing, cleaning and tidying. Those who could not match up often received a ‘scrubbing’, an involuntary wash with ‘Pusser’s Hard’ soap, or sand soap, and hard brooms and scrubbing brushes. For JRs on the receiving end of such a scrubbing it was humiliating and painful.

Similarly, throughout the RAN there was a stigma attached to being a too-frequent visitor to the sick bay. Those who did were labelled ‘sick bay jockeys’ and combined with the fact that a visit to the sick bay was never a pleasant experience this produced a culture in which JRs would endure ailments and only seek medical aid when instructed to do so or when the nature or severity of their complaint made it unavoidable. However, the health of junior recruits was of a relatively high order. A reasonably well-balanced diet, an energetic lifestyle with a strong emphasis on sport, ready access to medical and dental treatment and the naval fixation with neatness and cleanliness all helped prevent illness and provide a ready cure when it did occur.

Recreation

Records show that throughout the life of the junior recruit training scheme Leeuwin’s staff members were very conscious of the need to put more into the JR’s lifestyle than regimentation and study. Leeuwin’s commanders and many individual staff members tried hard to provide activities that distracted and diverted the JRs from a lifestyle in which they were confined for almost a year, in large numbers, to a small geographical area, under supervision for much of each day and subject to formal and informal discipline regimes that, if misapplied, would have undesirable outcomes. The difficulty in enriching their lives increased as the size of the junior recruit population grew, as the ratio of staff members to JRs diminished and as the training curricula began to focus more narrowly on naval training rather than academics.

Leeuwin Staff

At Leeuwin, civilians undertook a limited range of administrative and support work and, as Leeuwin did not have sufficient uniformed staff members to perform all the establishment’s domestic duties, all junior recruits had to share the daily burden of cleaning, fetching and carrying, food preparation and general labouring.

Leeuwin’s ship’s company was organised in much the same way as the RAN’s other large training bases. Commanded by a commodore rank officer ‘dual-hatted’ as CO and NOICWA or NOCWA, it included Executive, Supply, Engineer, Medical and Instructor departments. Civilian psychologists and social workers were permanent members of the work force to cope with the collective needs of the JRs and staff members. Leeuwin had an unusually large academic staff of uniformed instructor officers and senior sailor rank Academic Instructors to operate what was essentially a small junior high school required to deliver the academic components of the normal and advanced training streams. To address the naval elements of these streams Leeuwin had a seamanship school, a physical training section, a gunnery school responsible for drill and weapons training, staff to provide instruction in atomic, biological and chemical defence and damage control and a Chief Petty Officer Musician to train and operate the junior recruit drum and bugle band. In addition to their primary duties many officers and sailors shared responsibility for such things as first aid training, discipline and regulating, and branch familiarisation training intended to assist JRs to make informed decisions about their choice of employment category post-Leeuwin.

The heavy training work load, staff shortages, very high levels of responsibility for the most junior ranks and few opportunities for leave would not have made Leeuwin a popular posting choice. Critical references regarding the quality of the junior recruits’ lifestyle and the need to do more for them would have been both irritating and demoralising for a staff working hard to cover the gaps caused by shortages and to provide a good training experience for the JRs.

The nature of relationships between the JRs and staff members varied considerably. At the basic level it was formal as, most unusually, all staff members regardless of their rank were called ‘sir’ by the JRs, a practice objected to in the Fleet where it was carried over improperly by former junior recruits for whom it had become a deeply ingrained and highly undesirable habit. The JR’s subjection to the Naval and Defence Force Discipline Acts combined with a pervasive and unrelenting Leeuwin focus on obedience, neatness, cleanliness, conformity and the need to prepare for life at sea in a warship, inhibited the formation of more personal relationships between JRs and staff members. In consequence, junior recruit attitudes toward staff members also varied. JRs liked, or at least cooperated well with, staff members who were fair, compassionate and slow to punish. They disliked and feared those whose response to any minor indiscretion was punishment, which could be formal or informal and was often physical. Leeuwin was fortunate to have many staff members in the former category who set a fine example and were role models in every respect. Members of each intake have memories of a good sprinkling of individuals whose behaviour and treatment of the JRs was exemplary. Examples of such men is Petty Officer Sick Berth Attendant Ken Hay who served as a divisional staff member at Leeuwin in the late 1960s. Lieutenant Commander ‘Johno’ Johnson, a transferee from the Royal Navy and Leeuwin’s long-term Gunnery Officer is another.

Some staff members were unpopular among junior recruits not for their real or perceived individual failings but because of the nature of their duties. It is fair to say that gunnery and physical training instructors seldom attracted JR’s affection simply because of the physical nature of the activities they conducted and their capacity, and freedom, to raise its tempo to a level where it became a painful and exhausting form of informal punishment. Regulating staff were another category for whom the JRs usually had little time. At leave parades it was they who decided whether a boy’s uniform was of a sufficient standard to be allowed ashore in. An infuriating delay and loss of leave would often occur as a boy was sent back to his accommodation to remedy the deficiency and wait to report for a further inspection at the time of the staff member’s choice. Staff members who resorted to group punishments for minor rule infringements by individuals were also heartily disliked. One boy skylarking after pipe down could result in the entire population of one floor of a block being turned out in pyjamas to double around the parade ground with kit bags or mattresses held above their heads. Whilst the influence of well-liked staff members probably skewed the category decisions made by some Leeuwin JRs.

That Leeuwin operated for 24 years with very few calamitous events or abuses of the thousands of JRs who passed through it suggests that on balance the quality of staff was good. Seen with 21st century eyes many aspects of Leeuwin training, lifestyle and culture seem old-fashioned, overly regimented and harsh, particularly those that existed in the 1960s. However, Leeuwin did respond to changes taking place in Australian society and in the RAN itself. Staff performance and attitudes that existed towards the end of the scheme are likely to have differed markedly from those present at its start. The most fitting accolade for Leeuwin’s staff was probably that expressed by the NOCWA handing over command in January 1975 who said:

I must also pay tribute to the officers, senior sailors, and junior sailors who staff the Junior Recruit Training Establishment. These men spend long hours outside normal working hours and over weekends ensuring that Junior Recruits are kept actively and usefully occupied. The Service owes these men much because it is on the results of their efforts that the quality of the bulk of the Navy’s manpower depends.

Recruiting of Minors

From the earliest days of WWI and the Tingira scheme the Navy deployed JRs to war. The last WWI deployment occurred:

On 17th July 1918, the last wartime draft for overseas service from Tingira embarked on the troopship Borda for England for distribution to HMAS Australia, Melbourne and Sydney. This draft totalled 50 JRs, of whom 31 were 15 years old, 14 were 16 years old.’

JRs entering the Navy in the 1960s experienced similar treatment. Many 15-year-old JRs who entered the Navy in the 14th intake and subsequent junior recruit intakes into the early 1970s qualified for war service as 17-year-old boy ordinary seamen and midshipmen in the troop transport Sydney. A much smaller number of JRs served as 17-year-olds in Vietnam in the guided missile destroyers HMA Ships Perth, Hobart and Brisbane and the destroyer HMAS Vendetta.

Australia’s freedom to employ JRs on operations ceased on 20 October 2002 when the Australian Ambassador to the United Nations signed the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict. As a signatory to the Protocol Australia agreed to abide by a new standard which set a minimum age of 18 for participation in hostilities and a voluntary minimum age of 16 for recruitment into the Australian Defence Force (ADF). However, the ADF observes a minimum recruitment age of 17 except for ‘military schools’ that are defined as places where military personnel receive instruction. This exemption permits the recruitment of 16-year-olds to study in military schools but not for participation in hostilities.

The End of Boy Sailors

Despite the perceived and real problems of the boy sailor entry scheme its reintroduction had the intended strategic effect of making the RAN more attractive to a large number of boys who otherwise may never have considered a naval career. Without the scheme the RAN’s acute staffing crisis would have continued for much longer as adult recruiting performance failed to meet demand. It is therefore questionable whether the Navy could have successfully introduced new submarines, the Perth class guided missile destroyers and maintained the Fleet Air Arm without the sudden influx of large numbers of JRs through the junior recruit scheme.

The aim of the junior recruit entry being a source of senior sailors and officers seems to have been achieved. Given the high retention rates of junior recruits until 1973 it is likely that a great many would have become senior sailors in at least the normal course of their sailor advancement processes, if not earlier because of the age and higher educational achievement. The aim of producing sailors who could make the often-difficult transition to officer also seems to have been achieved. In 1972 for example, of the 27 matriculants who entered the RANC nine were graduates of the Leeuwin officer candidate course. As outlined in the Appendix, between 1964 and 1984, at least 255 JRs, 2 per cent of Leeuwin graduates, were transferred to officer candidate training.

In addition to these JRs, many ex-junior recruits went on to become officers later in their careers through the Special Duties List, the Warrant Officer Entry Scheme and the New Entry Officer Scheme. By 2001, three former junior recruits had reached the rank of commodore, and of these two were later promoted to the rank of rear admiral. One of them, Russell Crane, a member of the 32nd intake entered on 15 July 1970, was promoted to Vice Admiral and appointed Chief of Navy in July 2008, a unique and remarkable achievement.

Measuring the contribution junior recruits would certainly have made to improving the Navy’s capacity to use new technology is very difficult. As the Appendix shows, between 1964 and 1984 at least 299 JRs, about 3 per cent of all graduates, left Leeuwin either before or upon graduation to undertake apprentice training at Nirimba. This ‘internal recruiting’ no doubt boosted the numbers of highly trained technical senior sailors in the Navy but, as some have argued, at the expense of increasing the technical capacities of the Navy’s junior sailor workforce.

The final passing out parade for Leeuwin junior recruits occurred held on 4 December 1984 when 37 JRs of the 86th intake of junior recruits graduated. The reviewing officer was Rear Admiral William Crossley, Chief of Naval Personnel, who, having joined the Navy as a sailor in 1954, had the distinction of being the first man to rise through the sailor ranks to become an officer and achieve flag rank.

Leeuwin was decommissioned as a naval base on 11 November 1986, but it has continued to play a role in what has become a large Defence presence in Western Australia.

Junior Recruits Today

The junior recruit training scheme began and ended within living memory. The oldest former junior recruit was only 67 on the 50th anniversary of the scheme’s commencement in July 2010, while the vast majority of JRs who joined via the scheme are still alive. Many still serve in the ADF and many will continue to do so until 2024 when the youngest member of the final intake, the 86th, would have completed 40 years of military service and be 55-years-old. However, given that the compulsory retirement age of the ADF has been increased from 55 to 60 and it employs reservists until the age of 65, it is possible that former junior recruits may still be serving until about 2034.

While immensely proud of having joined and served their country it is not uncommon to hear expressions of regret about having made a commitment while so young and, in doing so, foregoing other career options that might have suited them better in the long run. Extreme manifestations of this view produce accusations that ‘the Navy stole my youth’ but in reality, there was no compunction to join, the scheme was entirely voluntary and very popular with JRs and their parents, to the extent that for most of the scheme’s existence the RAN could afford to be quite selective about who could join and who could not.

For better or worse, it was the JRs and their parents who made the decision; the RAN was simply a very willing beneficiary at a time in Australian history when early commitment to a lifelong career was commonplace. Paradoxically, regret over the decision to join so young and forego other opportunities often co-exists with a strong sense of pride in actually having joined and served. Many consider that their exposure to an adult environment, being forced to sever some family bonds very early and to accept responsibility for themselves gave them a head start in life overall and in the RAN. Many attribute achievements, such as early promotion to higher sailor rank, grasping the many opportunities for education and training the Navy offered, transferring to officer training and experiencing, at a young age, things that many other young Australians would never have the opportunity to do, during their training at Leeuwin or Cerberus.

Whilst ex-sailors will generally identify themselves in relation to a particular employment branch or category within the RAN, a rank or to membership of a particular ship’s company, junior recruits identify themselves as members of a particular intake and whether that intake passed through Leeuwin or Cerberus. The experience of living together as an intake for a year, starting as ‘new grubs’ and progressing through the informal junior recruit seniority system reinforced intake identity. Doing so in close company, in a challenging training environment helped forge strong, life long bonds of friendship among many junior recruits. The intake orientation endures today.

Annex A provides a record of the number of young Australians who participated in the Junior Recruit Training and Education scheme.

This paper is a precis of “HMAS LEEUWIN: The Story of the RAN’s Junior Recruits” as well as personal memories from the 47th Intake. The full story of the RAN Junior Recruits has been written by Brian Adams for the Sea Power Centre – Australia. The full document is located at “Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No 29” and can be read at www.navy.gov.au/spc.

Annex A

| Intake Number | Date of Entry | Date of Graduation | Number of JRs Entered (see note 1) |

Total Number Graduated (see note 2) |

% Pass Rate (see note 3) |

To Officer Training | To Apprentice Training |

| Leeuwin | |||||||

| 1 | 13 Jul 1960 | 16 Jun 1961 | 155 | 142 | 92% | N/A (see Note 4) |

|

| 2 | 10 Jan 1961 | 13 Dec 1961 | 151 | 142 | 94% | N/A | |

| 3 | 12 Jul 1961 | 15 Jun 1962 | 155 | 143 | 92% | N/A | |

| 4 | 7 Jan 1962 | 12 Dec 1962 | 154 | 134 | 87% | N/A | |

| 5 | 11 Jul 1962 | 12 Jun 1963 | 179 | 142 | 79% | N/A | |

| 6 | 9 Jan 1963 | 11 Dec 1963 | 180 | 162 | 90% | ||

| 7 | 10 Jul 1963 | 10 Jun 1964 | 201 | 187 | 93% | ||

| 8 | 8 Jan 1964 | 9 Dec 1964 | 205 | 162 | 79% | 19 Topmen (see Note 5) |

|

| 9 | 8 Jul 1964 | 9 Jun 1965 | 201 | 181 | 90% | (see Note 6) | |

| 10 | 6 Jan 1965 | 8 Dec 1965 | 204 | 175 | 86% | 15 Topmen (see Note 7) |

|

| 11 | 7 Apr 1965 | 30 Mar 1966 | 102 | 86 | 84% | ||

| 12 | 14 Jul 1965 | 8 Jun 1966 | 204 | 182 | 89% | ||

| 13 | 13 Oct 1965 | 4 Oct 1966 | 104 | 89 | 86% | ||

| 14 | 5 Jan 1966 | 7 Dec 1966 | 203 | 177 | 87% | 15 (see Note 8) |

|

| 15 | 6 Apr 1966 | 29 Mar 1967 | 104 | 92 | 88% | ||

| 16 | 13 Jul 1966 | 7 Jun 1967 | 207 | 194 | 94% | ||

| 17 | 12 Oct 1966 | 3 Oct 1967 | 104 | 89 | 86% | ||

| 18 | 2 Jan 1967 | 6 Dec 1967 | 207 | 189 | 91% | 21 (see Note 9) |

|

| 19 | 5 Apr 1967 | 27 Mar 1968 | 105 | 82 | 78% | ||

| 20 | 12 Jul 1967 | 4 Jun 1968 | 208 | 179 | 86% | ||

| Intake Number | Date of Entry | Date of Graduation | Number of JRs Entered (see note 1) |

Total Number Graduated (see note 2) |

% Pass Rate (see note 3) | To Officer Training | To Apprentice Training |

| 21 | 11 Oct 1967 | 2 Oct 1968 | 100 | 83 | 83% | ||

| 22 | 3 Jan 1968 | 11 Dec 1968 | 209 | 201 | 96% | ||

| 23 | 3 Apr 1968 | 25 Mar 1969 | 110 | 86 | 78% | 9 | 2 |

| 24 | 10 Jul 1968 | 10 Jun 1969 | 210 | 197 | 94% | ||

| 25 | 9 Oct 1968 | 23 Sep 1969 | 100 | 76 | 76% | 9 | 7 |

| 26 | 8 Jan 1969 | 9 Dec 1969 | 200 | 181 | 91% | 7 | 5 |

| 27 | 9 Apr 1969 | 24 Mar 1970 | 110 | 97 | 88% | 4 | 1 |

| 28 | 16 Jul 1969 | 9 Jun 1970 | 210 | 168 | 80% | 4 | 9 |

| 29 | 15 Oct 1969 | 22 Sep 1970 | 110 | 87 | 79% | 3 | 7 |

| 30 | 7 Jan 1970 | 8 Dec 1970 | 252 | 193 | 77% | 11 | 17 |

| 31 | 15 Apr 1970 | 23 Mar 1971 | 183 | 140 | 77% | 3 | 7 |

| 32 | 15 Jul 1970 | 8 Jun 1971 | 191 | 140 | 73% | 8 | 1 |

| 33 | 13 Oct 1970 | 21 Sep 1971 | 145 | 103 | 71% | 3 | 7 |

| 34 | 6 Jan 1971 | 7 Dec 1971 | 250 | 175 | 70% | 11 | 15 |

| 35 | 13 Apr 1971 | 21 Mar 1972 | 209 | 142 | 68% | 8 | 4 |

| 36 | 14 Jul 1971 | 6 Jun 1972 | 192 | 153 | 80% | 2 | 7 |

| 37 | 16 Oct 1971 | 19 Sep 1972 | 129 | 95 | 74% | 3 | 8 |

| 38 | 3 Jan 1972 | 12 Dec 1972 | 207 | 167 | 81% | 6 | 8 |

| 39 | 10 Apr 1972 | 27 Mar 1973 | 189 | 158 | 84% | 3 | 6 |

| 40 | 10 Jul 1972 | 12 Jun 1973 | 196 | 157 | 80% | 0 | 5 |

| 41 | 9 Oct 1972 | 25 Sep 1973 | 188 | 135 | 72% | 4 | 6 |

| 42 | 10 Jan 1973 | 11 Dec 1973 | 254 | 205 | 81% | 10 | 9 |

| 43 | 16 Apr 1973 | 26 Mar 1974 | 200 | 176 | 88% | 1 | 1 |

| 44 | 16 Jul 1973 | 11 Jun 1974 | 224 | 178 | 79% | 3 | 9 |

| 45 | 15 Oct 1973 | 24 Sep 1974 | 100 | 86 | 86% | 3 | 0 |

| 46 | 2 Jan 1974 | 10 Dec 1974 | 190 | 164 | 86% | 10 | 3 |

| 47 | 22 Apr 1974 | 25 Mar 1975 | 163 | 128 | 79% | 3 | 5 |

| 48 | 15 Jul 1974 | 10 Jun 1975 | 142 | 121 | 85% | 0 | 0 |

| Intake Number | Date of Entry | Date of Graduation | Number of JRs Entered (see note 1) |

Total Number Graduated (see note 2) |

% Pass Rate (see note 3) | To Officer Training | To Apprentice Training |

| 49 | 14 Oct 1974 | 23 Sep 1975 | 151 | 117 | 77% | 2 | 5 |

| 50 | 8 Jan 1975 | 9 Dec 1975 | 276 | 229 | 83% | 7 | 13 |

| 51 | 1 Apr 1975 | 23 Mar 1976 | 172 | 119 | 69% | 5 | 7 |

| 52 | 14 Jul 1975 | 8 Jun 1976 | 215 | 188 | 87% | 4 | 4 |

| 53 | 13 Oct 1975 | 21 Sep 1976 | 143 | 113 | 79% | 4 | 4 |

| 54 | 7 Jan 1976 | 7 Dec 1976 | 252 | 211 | 84% | 7 | 1 |

| 55 | 20 Apr 1976 | 22 Mar 1977 | 188 | 131 | 70% | 1 | 17 |

| 56 | 14 Jul 1976 | 7 Jun 1977 | 197 | 168 | 85% | 0 | 5 |

| 57 | 11 Oct 1976 | 20 Sep 1977 | 164 | 131 | 80% | 2 | 3 |

| 58 | 3 Jan 1977 | 13 Dec 1977 | 260 | 207 | 80% | 6 | 3 |

| 59 | 12 Apr 1977 | 21 Mar 1978 | 205 | 145 | 71% | 3 | 14 |

| 60 | 11 Jul 1977 | 6 Jun 1978 | 173 | 142 | 82% | 0 | 5 |

| 61 | 11 Oct 1977 | 6 Jun 1978 | 120 | 99 | 83% | 0 | 0 |

| 62 | 11 Jan 1978 | 19 Sep 1978 | 120 | 96 | 80% | 3 | 6 |

| 63 | 10 Apr 1978 | 12 Dec 1978 | 60 | 53 | 88% | 1 | 7 |

| 64 | 10 Jul 1978 | 20 Mar 1979 | 61 | 54 | 89% | 1 | 3 |

| 65 | 10 Oct 1978 | 12 Jun 1979 | 90 | 79 | 88% | 0 | 3 |

| 66 | 10 Jan 1979 | 18 Sep 1979 | 120 | 107 | 89% | 2 | 7 |

| 67 | 9 Apr 1979 | 11 Dec 1979 | 120 | 104 | 87% | 0 | 4 |

| 68 | 15 Jul 1979 | 18 Mar 1980 | 60 | 52 | 87% | 0 | 3 |

| 69 | 9 Oct 1979 | 10 Jun 1980 | 60 | 57 | 95% | 0 | 0 |

| 70 | 9 Jan 1980 | 16 Sep 1980 | 60 | 51 | 85% | 1 | 3 |

| 71 | 8 Apr 1980 | 9 Dec 1980 | 60 | 54 | 90% | 0 | 0 |

| 72 | 14 Jul 1980 | 9 Mar 1981 | 60 | 57 | 95% | 0 | 0 |

| 73 | 1 Oct 1980 | 9 Jun 1981 | 60 | 57 | 95% | 1 | 4 |

| 74 | 7 Jan 1981 | 15 Sep 1981 | 60 | 48 | 80% | 1 | 3 |

| 75 | 7 Apr 1981 | 8 Dec 1981 | 60 | 52 | 87% | 1 | 0 |

| 76 | 14 Jul 1981 | 16 Mar 1982 | 80 | 66 | 83% | 0 | 5 |

| Intake Number | Date of Entry | Date of Graduation | Number of JRs Entered (see note 1) |

Total Number Graduated (see note 2) |

% Pass Rate (see note 3) | To Officer Training | To Apprentice Training |

| 77 | 1 Oct 1981 | 9 Jun 1982 | 80 | 67 | 84% | 2 | 6 |

| 78 | 1 Jan 1982 | 14 Sep 1982 | 90 | 80 | 89% | 2 | 4 |

| 79 | 14 Apr 1982 | 7 Dec 1982 | 90 | 80 | 89% | 1 | 0 |

| 80 | 12 Jul 1982 | 15 Mar 1983 | 90 | 83 | 92% | 0 | 2 |

| 81 | 6 Oct 1982 | 8 Jun 1983 | 90 | 76 | 84% | 0 | 1 |

| 82 | 4 Jan 1983 | 20 Sep 1983 | 71 | 61 | 86% | 0 | 5 |

| 83 | 6 Apr 1983 | 6 Dec 1983 | 70 | 66 | 94% | 0 | 0 |

| 84 | 5 Jul 1984 | 12 Mar 1984 | 71 | 60 | 85% | 0 | 1 |

| 85 | 10 Jan 1984 | 18 Sep 1984 | 40 | 36 | 90% | 0 | 2 |

| 86 | 3 Apr 1984 | 4 Dec 1984 | 40 | 37 | 93% | 0 | 0 |

| Cerberus | |||||||

| 1 | 17 Mar 1963 | 26 Mar 1964 | 125 | 123 | 98% | ||

| 2 | 6 Apr 1964 | 1 Mar 1965 | 200 | 198 | 99% | ||

| Overall Totals | 13000 | 10875 | 84% | 255 | 299 |

Notes:

- The ‘Numbers of Boys Entered’ are derived from HMAS Leeuwin Reports of Proceedings (ROPs). However, these documents do not record numbers entered for intakes 3, 6, 22 and 24. These numbers were derived from Navy recruiting intake lists and unofficial class lists.

- The ‘Total Number Graduated’ entries are derived from HMAS Leeuwin ROPs. However, these documents do not record numbers for intakes 1 to 4, 9 and 10, 12, 14, 16 to 19, 21 and 22 and 24. These numbers were derived from passing out parade handbooks.

- The ‘% Pass Rate’ does not include the numbers of junior recruits selected for officer candidate and apprentice training. Inclusion of these numbers increases the pass rate to 87%.

- The Topmen training scheme was introduced in January 1963.

- This number is that mentioned in the HMAS Leeuwin ROP for the period 1 January to 31 March 1964.

- The first transfer of boys from junior recruit training to apprentice training occurred in 1964.

- This number is that mentioned in the HMAS Leeuwin ROP for the period 1 January to 31 March 1965.

- This is the number of Topmen shown in the Topmen Division photograph in the 14th Intake passing out parade book, December 1966.

- This is the number of Topmen shown in the Topmen Division photograph in the 18th Intake passing out parade book, December 1967.